30 October 2008

The Significance of the Journey in 20th Century Middle Eastern Literature

When most people think of a journey, they think of traveling and experiencing various cultures. In Naguib Mahfouz’s The Journey of Ibn Fattouma, the journey represents much more. Qindil, the protagonist, travels on a simultaneous inner and outer journey. Superficially, he is experiencing new people, beliefs, and cultures, but he is also changing as the journey continues. He is evolving into a new man with every experience; he is traveling toward perfection.

Initially, Qindil explains, “During his discourse he [Sheikh Maghagha al-Gibeili] talked about a certain ancient traveler…He spoke so liberally that I lived in my imagination the vast lands of the Muslims, and my own homeland seemed to me like a star in a sky crammed with stars” (5). From these quotes, the narrator is foreshadowing the never-ending journey of Qindil; it’s like the vast celestial universe. The Sheikh recalls his own journey and his regrets. The Sheikh states, “The circumstances of life and family made me forget the most important objective of the journey, which was to visit the land of Gebel…It’s as though it were the miracle of countries, as though it were perfection itself, incomparable perfection” (6). From these lines, the audience can sense that Qindil is intrigued and mesmerized by the description. Qindil will not be stopped by “the circumstances of life and family.” He will reach the most important objective; he will see Gebel.

Next, through Qindil’s responses and questions, the audience is privy to his thought processes. He has a desire to explore, to see, and possibly the propensity to evolve. The Sheikh continues describing his personal journey. He recalls, “I have never in my life…met a human being who has paid it a visit, nor have I found a book or manuscript about it [Gebel]...It’s a closed secret” (6). From this quote, the audience assumes that Gebel represents the obscurity of knowledge. The narrator writes, “And like any closed secret it drew me to its edge and plunged me into its darkness. My imagination was fired. Whenever I was upset by a word or action, my soul fluttered around the land of Gebel” (6-7). From these quotes, the audience becomes aware of the continual foreshadowing.

The rising action of the novel is preparing the audience for Qindil’s upcoming travels. Losing Halima Adli at-Tantawi is the catalyst Qindil needed to journey and appease his soul and his desire. The narrator writes, “An inner voice told me that I would be the first human being to be given the chance of touring the land of Gebel and making known its secrets to the world” (22). The true journey is his journey into the exploration of Islam.

Furthermore, Qindil’s journey into Islam is foreshadowed in the first few pages. Qindil asks, “If Islam is as you say it is, why are the streets packed with poor and ignorant people?” (4). The Sheikh answers, “Islam today skulks in the mosques and doesn’t go beyond them to the outside world” (4). As a result, Qindil remarks, “Then it is Satan who is controlling us, not the Revelation…I am upset by injustice, poverty, and ignorance” (4, 7). From the dialogue, the audience is able to see how Qindil’s perceptions are forming; the audience is cognizant of the ideas that are growing in his consciousness. Qindil will not practice Islam in the mosques; he will search for it and analyze it during his journey. Thus, the journey is a search for meaning, but it is also an evolution of character and faith.

The journey is an experience that Qindil relishes. Each experience represents a new lesson, a new step in evolving. In Mashriq, Qindil experiences the polar opposite of the teachings of Islam; he witnesses nudity and idol worship. He asks, “What land is this that hurls a young man like me into the flames of Temptation!” (23). From the quote, the audience realizes that this is a new experience for Qindil.

Next, he reveals, “I pondered over the torments suffered by human beings in this life and wondered [if] in fact there was to be found in the land of Gebel the elixir for all ills” (29). From the quote, the audience realizes that Qindil is learning and growing. He asserts, “I gave myself over to my thoughts in a miserable state of languor until, all of a sudden, my ear was pierced by a shout for help. I jump to my feet in a state of readiness and found myself in utter darkness. I quickly grasped that I had been asleep, that in fact sleep, that in fact sleep was covering the whole universe. I had awoken early” (33). As proof of his evolution, he senses some awareness of being in darkness as well as the state of his surrounding. He is obtaining knowledge. The lack of religion in Mashriq aids him in obtaining a clearer picture of Islam.

Also, he also experiences the turbulence of a romantic relationship with a pagan woman, Arousa. He realizes that it is a personal choice to follow Islam; she makes a choice not to practice the faith. In essence, one must choose Islam; it does not choose you. In Haira, Qindil experiences the cause-and-effect of war and the elation of freedom. It can be implied that he learns that Islam represents freedom from bondage which can not be paid for, as illustrated in his failed attempt to purchase Arousa. There are many implications, but one idea is solid; he is experiencing and evolving on his journey.

In Halba, Qindil attempts love once more with Samia, a Muslim female pediatrician. With Samia, Qindil learns to respect Islam, but abandons a present love for a past love. This could parallel to his love of Islam; he must not forsake his first love, Islam. Next, Qindil journeys to Aman where freedom is suppressed. Thus, Islam is suppressed. Finally, it is in Ghuroub that Qindil prepares for his “beginning” in Gebel. Ghuroub represents the love of reason and logic, knowledge and wisdom. Here Qindil is able to evolve, grow, and prepare for Gebel, to achieve perfection. The Sheikh prophesy of “never [having]…met a human being who has paid it a visit, nor have I found a book or manuscript about it...It’s a closed secret” is realized (6). The audience will never know the secret, but possibly Qindil will know it. Qindil has the opportunity to reach perfection and obtain the secret of Gebel.

In essence, initially Qindil “pondered about how we embellish our longings with luminous words of piety, and how we conceal our shyness with firebrands of dive inspiration” (13). But slowly, with each journey within the journey, he progresses and obtains enlightenment. This assertion is implied in the very first lines of the novel. The narrator states, “Life and death, dreaming and wakefulness: stations for the perplexed soul. It transverses the stage by stage, taking signs and hints from things, groping about in the sea of darkness, clinging stubbornly to hope that smilingly renews itself” (1).

In sum, the first lines tell why Qindil must journey for so long. He must learn lessons from each experience; he must evolve into a new man. With each journey, his faith increases and strengthens as he reaches for perfection.

28 October 2008

Response to Palmer’s The Promise of the Father: Chapter One (Rhetoric and Composition)

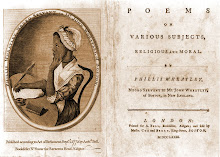

The Promise of the Father by Phoebe Palmer is an “argument in defense of women’s public ministry” (1089). She begins her argument by stating “Do not be startled…We do not intend to discuss the question of ‘Women’s Rights’ or of ‘Women’s Preaching,’” but, in a sense, that is exactly what she does; it is simply veiled by religious activity.

The text is full of the words: we, us, and our. Additionally, she poses some fifteen rhetorical questions and uses numerous enthymemes. Palmer is definitely making a connection. She is placing all women in the same situation that she faces as she attempts to promote God’s word. Yet she attempts to assure men that she does not aim to take their leadership roles; she is simply doing God’s will. Yet near the end of the text, she contradicts those statements.

Initially, she states, “But we have never conceived that it would be subservient to the happiness, usefulness, or dignity of woman, were she permitted to occupy a prominent part in legislative hall, or take a leading position in the orderings of church conventions. Ordinarily, these are not the circumstances where woman can best serve her generation according to the will of God” (1095).

But she asserts, “It is in the order of God that woman may occasionally be brought out of the ordinary sphere of action, and occupy in either church or state positions of high responsibility…The God of providence will enable her to meet the emergency with becoming dignity, wisdom, and womanly grace.”

Toward the middle of the text, she assures men that Adam was before Eve, and men were in a superior position and are the “first in creation, long as time endures.”

However, in the end she states, “Not only will the women of this age have to do with the women of the future age, but, as the men of the future age will have had their early training mostly from the women of the present age, how greatly have women to do with the destines of the moral and religious world!” (1099).

In order to back her claim, she proceeds to give biblical examples of where women served in Christian leadership roles. She mentions Deborah, a judge of Israel who was instrumental in leading a fierce, but victorious battle. Palmer states, “She led forth the armies of God to glorious conquest…not because there were not men in Israel [but because of her faith and wisdom.]”

She asserts that Huldah, the prophetess who proclaimed Jesus as the Messiah, was sought out for council by the king because she possessed the “momentous trust, involving the destinies of her country” (1096). She goes on to mention Queen Victoria and Mary as well.

After backing her claims with “modern and ancient” examples, she goes on to address to origin of the conflict on whether or not women should minster the word of God. But first she addresses the naysayers. She reminds her audience that no one ever questioned whether or not the women mentioned above could lead; instead, “we only speak of their being pious, earnest, [and] Christian wom[en].”

Then she poses the question, “Whose head the tongue of fire has descended” and who would have Christian women silenced? She states, “It is the power of an ever-present Jesus that the Spirit would have her testify; but the seal of silence has been placed on her lips. And who has placed the seal of silence on those Heaven-touched lips? Who would restrain the lips of those whom God has endued with the gift of utterance...?”

She addresses the origin of the conflict. She dissects Paul’s letter as it related to the women of Corinth. She argues that Paul’s instructions where specific for that particular church, not all women in all churches. In essence, she effectively used rhetoric to argue a point in a logical and methodical way. She gradually elevated the tension within the text through words, rhetorical questions, and stories. She systematically took apart the argument that women should not minister God’s word.

In the last paragraph, the text climaxes, she names her accusers. She states, “We feel that there is a wrong…which has long been depressing the hearts of the most devotedly pious women. And this wrong is inflicted by pious men [who] imagine that they are doing God service in putting a seal upon lips which God has commanded to speak…But…as we believe ignorance they have done it. Now ignorance will involve guilt” (1099). Palmer’s argument is a call to action for both women and men.

17 October 2008

A Reader–Response Criticism: Meant to be Appreciated (Southern Literature)

Today, when the temperature changes and the season becomes anew, it is easy to remember living in a rural Georgia community. What I do recall is that although the area lacked an abundance of extracurricular facilities for its youth, it was rich in other things—tradition, heritage and family—and stagnant but as colorful as an old hand-worked quilt in any home, even today. These quilts can be found in every home. I have several in my possession as well. Some were given to me as gifts for various occasions from my grandmothers, my aunts, my mother and the church “sisters” from our community. In my family, the trade of quilting has been passed down for generations.

As stated in the analysis “In Spite of It All: A Reading of Alice Walker’s ‘Everyday Use’” in the African American Review, Sam Whitsitt quoted Barbara T. Christian’s assertion that “the metaphor of quilting to represent the creative legacy that African Americans have inherited from their maternal ancestors” (443). Alice Walker has been instrumental in analyzing the value of the quilt in the black experience. Most black experiences are unique yet similar, for instance many share life experiences. I remember from my parent’s backyard, I could see a family pond that was surrounded by the homes of my relatives. It still exists today as an 84 acre plot of houses owned and operated, with small gardens on the side or in the back, by family members. I shared that experience with two siblings and sixty three cousins.

Characterized by personal development, social elevation and cultural awareness, Alice Walker presented a distinct analysis of these concepts in the short story “Everyday Use.” Being caught in the middle of two ideologies were three family members, Mrs. Johnson, Maggie and Dee/Wangero. The vastness of the short story can be analyzed through the reader-response approach. Recognizing that different readers will have different responses to the work of literature at variable life stages and life experiences that are specific to the reader’s evaluation of the text. The characteristics of personal development, social elevation and cultural awareness of the three main characters, Mrs. Johnson, Maggie and Dee/Wangero will be discussed and examined.

This year, during my re-entrance into the collegiate setting in English studies, I, a young African-American woman from the South—a second career advent—was delighted to choose a career path beyond that of Respiratory Therapy. I had truly believed my calling to be a clinician but I had not truly appreciated my uniqueness and love of literature and spoken word. With the enthusiasm of a recent student, I am challenging my beliefs and reconsidering the understandings of my Southern history and traditions, to “revise [my] notions of what constitutes [a] sense of place, political agenda, race and class" (630). I was born and reared in Roberta, Georgia, which is approximately a forty-five minute drive from Eatonton, Georgia, where Alice Walker was born and reared (556). As a child, my mother loved to read poems written by Walker, as she thought television to be the death of us.

While reading Steven Mailloux’s Reading in Critical Theory, I realized each reader responds differently to the text. My reading of Alice Walker’s short story “Everyday Use” and my continuing evaluation of my childhood and my love of quilting has lead me to analyze my life and its place as it relates to the short story (1149). I began quilting around the age of ten, during the summer when school was not in session. My aunt never learned to knit or crochet, but she was a phenomenal quilter. Aunt Mattie Pearl Blasingame took a special interest in me. A quiet woman of menial means, Aunt Mattie Pearl sold quilts to aid in the financial status of her home. She was actually my great-great aunt but those specific distinctions were not routinely made in my family, then or now. She was not well educated and could read very little, but she had memorized passages of Scripture and could tell virtually every major story in the Holy Bible.

Financially and educationally deprived, Aunt Mattie Pearl was emotionally depressed as well. Creating meaning and experience to the text to be analyzed, her husband, Uncle Josephus, was a farmer and they had eleven children whom did not visit very often. Uncle Joe was a bit of a tyrant and suffered many of the emotional ills of black men of his day. He needed to control something; his obedient and submissive wife was the perfect victim. To further aid in processing the text, Aunt Mattie Pearl’s grand-daughter, Laura, commissioned her for quilts and obtained orders from everywhere. Laura was a recent graduate from Georgia College and State University in Milledgeville, Georgia. Not knowing the worth of the quilts, Aunt Mattie Pearl sold the quilts for $25.00 a piece. She was ecstatic and reveled in the financial gain, but her bruised hands told another story.

With her new found wealth, her life began to change. As a child, I could not understand why that part of the family was so odd. My mother would tell us that it was not Aunt Mattie Pearl, but “it was that crazy Uncle Joe.” She surmised he did not know any better and did not want any better. He alienated his family from the community. My father and uncles would go down and take food or offer to do handy man jobs around the house. Uncle Joe was old and unable to do any hard physical labor—the sight of their home told the story all too well—but he would refuse and would politely say “if I need ya, I’ll call ya”—they did not have a telephone. Constantly working to provide financial means for her family, Aunt Mattie Pearl would make three to four quilts a week. As soon as they were made, she would sell them. Aunt Mattie Pearl was always positive despite her circumstances. She always sang as she quilted. She was proud of her accomplishments and for the first time people commented on her wonderful smile. Why not rest, I once asked. “When the Lord gives you a way out, take it,” she responded and busily began a new quilt.

These memories with Aunt Mattie Pearl forced me to analyze my views of Alice Walker’s short story, not to mention to examine my own position about culture and heritage. If Mrs. Johnson was the uneducated woman living in rural Georgia and the matriarch of her family, Aunt Mattie Pearl was the antitype (631). If Maggie, the stay at home daughter in the story, was the meek and devoted daughter, Laura was the antitype. And if Dee/Wangero was the culturally aware and educated daughter, I was the antitype.

Both Mrs. Johnson and Aunt Mattie Pearl were family matriarchs: Mrs. Johnson supported her family and worked hard, along with the Church, to send Dee “to Augusta to school” (559). Likewise Aunt Mattie Pearl would make quilts and give Laura “spending change” while she matriculated Georgia College and State University. Both women were uneducated and living in rural communities in substandard housing. Both women took on the overseer role for their families. And both knew the importance of an education, despite not being able to obtain one themselves. They were stout women who desired the best for their families.

Both Maggie and Laura were devoted “daughters” in the truest sense of the word: Maggie stayed around the home and aided her mother in cleaning the yard and other domestic duties. Likewise Laura cared for her grandmother and desired to aid her in financial stability by soliciting orders for her quilts. She did not seek to change her grandmother or teach her a new trade. Instead she embraced what her grandmother knew well and helped her to make it profitable. Both women took on supportive roles and aided the matriarchs of their respective families.

Also like Maggie, Laura showed a sense of true cultural enlightenment in her appreciation and respect for character. Both women accepted the matriarchs in their family as they were and did not attempt to change or mold them into something better or more than they were. They simply embraced the person, not flowery notions of what they should be. Maggie remembered the stories of her ancestors and could recall them at will. Maggie was in touch with her family history and was deeply rooted in her heritage.

Both Dee and I possessed a cultural awareness that has been aided through education. Like Dee I have chosen to embrace the characteristics of my ethnicity; we both expressed this with natural hair texture. As in Dee’s childhood, I loved the audience of the family as I read and re-read stories. My family members listened intently and surely must have felt some “tiredness” of it all. Education was important to my family and they are still are a driving force for me.

Like Dee, I also appreciate my cultural and ethnic identity; but unlike Dee, I do not reject my personal history or try to exploit its circumstances. Mailloux asserted a component of a “reader-response criticism actually attempts to define a critical “movement” and therefore helps establish and disseminate it as well” (1150).

This is further explained by Barbara Christian in the first paragraph of her introduction of “'Everyday Use’ by Alice Walker” that “the Black Power Movement and the Second Wave of the Feminist Movement [are] two social interventions that define the literary commitments…and shape[d] our viewpoints about the social commitment to higher education (308). After this time period, African Americans exhibited a social commitment to higher learning. Dee was out-of-touch in her willingness to cling to a culture that she had not direct ties. By taking on the new name Wangero, and denying her generational name Dee, she lost touch with the concept of heritage. Her birth name had meaning and significant but Dee was unable to conceptualize that fact.

In Walker’s story, Dee has returned only to obtain certain items that she deemed historically and culturally valuable. Prior to embracing her family, she thought it necessary to take pictures of her mother, a cow, and the shack in which they lived. Dee was on a mission of sorts in order to obtain and secure their historical wealth—their heritage.

The house similar to the one she reveled as it burned to the ground became an architectural masterpiece. The bench that represented poverty as a child was now a piece of art. The irony and paradoxical duality of these occurrences brought to life her [Dee’s] out-of-touch personality. Mrs. Johnson noted the way Dee and Hakim-a-barber, her companion, had a conversation that was above her comprehension with their eyes.

Like Dee’s appreciation of the quilts, I display special quilts on my walls at my home. And occasionally on a quiet evening, I simply stare at them, appreciate them, and find a sense of peace. Unlike Dee/Wangero whose motives were a paradoxical irony—something she detested, she also wanted to preserve; something that was beneath her was something of supreme value. I believe Dee/Wangero was not sinister or evil but acted out of her need for preservation. She saw the value of her heritage and the main motive was of good origin--preservation of history. She realized that a remnant of a deep and rich past was bound in the quilts.

I am similarly interested in preserving the history of my family through restoration of family photographs and preservation of quilts and other items, for example, the copy of my great-grandparents wedding photo frame. Many critics have faulted Dee/Wangero for being out of touch with the needs of her family and attempting to exploit their ignorance to material value. I almost faulted her as well. Although I can identify with her efforts, I do not identify with her methods.

It had been years since I read the story of “Everyday Use” and now I have a clearer understanding and a newer appreciation for things of the past. These things matter and are a part of my culture. I recognize that the story of “Everyday Use” is a strong testament to my own history, “that this paper, if quilt-like in its narrative”, is a paradoxical and physical metaphor for the narrative and is designed to be displayed in our hearts, designed to be displayed on our walls and designed to be used every day, simultaneously (634).

Works Cited

Christian, Barbara T. “’Everyday Use’ by Alice Walker.” African American Review. 30.2 (1996): 308-309. JSTOR.16 October 2007 .

Mailloux, Steven. “Reader-Response Criticism: From Formalism to Post-Structuralism” Comparative Literature. 96.5 (1981): 1149-1159. JSTOR.16 October 2007 <>.

Torsney, Cheryl B. “Everyday Use: My Sojourn at Parchman Farm.” Literature and Its Writers: A Compact Introduction to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama. 4th ed. Ed. Ann Charters and Samuel Charters. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007. 630-634.

Whitsitt, Sam. “In Spite of It All: A Reading of Alice Walker’s ‘Everyday Use.’” African American Review. 34.3 (2000): 443-459. JSTOR.16 October 2007 < http://links.jstor.org/search>.

Walker, Alice. “Everyday Use.” Literature and Its Writers: A Compact Introduction to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama. 4th ed. Ed. Ann Charters and Samuel Charters. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007. 556-564.

16 October 2008

Shakespeare Character Analysis: The Character of Leonato in Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing (Shakespeare)

In casually reading Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, the play centers around six major characters: Don Pedro, Prince of Aragon; his companions Benedick, of Padua and Claudio, of Florence; Hero, Leonato’s daughter; Beatrice, Leonato’s niece; and Don John, the bastard brother of Don Pedro (1416). If one analyzes the text closely, it becomes obvious that the minor character Leonato, governor of Messina, makes all the necessary connections needed for the plot of Much Ado About Nothing to succeed.

The audience learns about Leonato through his words and responses. Observing the interactions of the six main characters, the governor of Messina is instrumental in the progression of the play. Through his verbal interactions, the audience perceives the full personality profile of Leonato. Throughout the rising action, climax, and resolution of the play, the character of Leonato is instrumental in every major scene and interacts with every major character. The governor’s importance and moral distinction are highlighted in the reception of the letter; the initial introduction and greeting of his guests; the guidance of his relatives; the interaction between other characters; and the response to his daughter’s dishonor.

Even though Leonato, governor of Messina, is a minor character, he accomplishes a great deal within the one hundred and twenty lines in which he is given. A superficial analysis of Leonato is needed in order to grasp the close reading of his words and responses. The character remains in the Messina, a Sicilian city, throughout the duration of the play; the entire plot plays out within the confines of his estate.

He is a round character that is original and memorable. Being dynamic, he experiences a transformation within the play. Leonato is hospitable to guests, concerned for loved ones, and an authority of what is just and fair. These superficial qualities allow the audience to perceive the deeper strengths in his character.

Leonato, the governor of Messina, opens the play by receiving a letter from a man of honor. He states, “I learn in this letter that Don Pedro of Aragon comes this night to Messina” (1.1.1-2). From these lines, the audience realizes that Leonato’s social position is important and that he is hospitable. Leonato eagerly makes preparations for his guests. Thus, Leonato’s response gives clues into his character.

Through his responses, the audience assumes that he is thoughtful and considerate, as well as important. The fact that Don Pedro is writing him and requesting temporary residence at his home conveys a sense of importance to the audience. In essence, the response, alongside his social standing, gives Leonato a trait that is characteristic of a compassionate man of importance. The characterization of Leonato makes the play possible or feasible in the eyes of the audience, and he is able to connect with the characters and the audience as well.

Moreover, the importance of Leonato is highlighted when he introduces the guests through his conversation with the messenger, and when he initially greets his guests on their arrival. He remarks, “A victory is twice itself when the achiever [Don Pedro] brings home full numbers. I find that Don Pedro hath bestowed much honour on a young Florentine called Claudio” (1.1.7-9). In these lines, Leonato is informing the audience of the major characters within the play. From the beginning, through Leonato, the audience knows the prestige associated with the visit.

Next, Leonato tells Beatrice, “Faith, niece, you tax Signor Benedick too much. But he’ll be meet with you, I doubt it not” (1.1.38-39). From this quote, the audience gains clues of the major character’s personalities. Furthermore, he explains to the messenger, “You must not, sir, mistake my niece. There is a kind of merry war betwixt Signor Benedick and her. They never meet but there’s a skirmish of wit between them” (1.1.49-51). Through these lines, the audience is given more information on the major characters, and the audience suspects a plot formation. Thus, elements of Leonato’s character are expounded on by displaying his position, words, and responses. Leonato introduces the major characters to the plot, and aids the audience in understanding the major characters.

Furthermore, it is Leonato who greets the guests; thus, his level of importance is expounded upon. The audience also glimpses his character as a human being through his words and responses in this interaction. Upon greeting his guests, Leonato implies the need for the social linguistics that take place between social authorities. Leonato states, “Never came trouble to my house in the likeness of your grace [Don Pedro]; for trouble being gone, comfort should remain, but when you depart from me, sorrow abides and happiness takes his leave” (1.1.80-83). Through the interaction, the audience further recognizes the “governly” status of Leonato.

Moreover, the governor addresses Don John, the bastard brother of Don Pedro, in the same manner of courtesy. He states, “If you swear, my lord, you shall not be forsworn. Let me bid you welcome, my lord. Being reconciled to the Prince your brother, I owe you all duty” (1.1.124-126). From these lines, the audience is aware of Leonato’s graciousness and social importance. He connects with the audience; when the major characters disappoint him, it is Leonato who commands the pity from the reader. Leonardo epitomizes a good human being. Through the greeting, the audience becomes aware of his graciousness and outstanding character. The greeting allows the audience to care about his state of being.

Also, the audience cares about the character of Leonato because he is concerned with the well-being of his family. Leonato provides guidance to his relatives. He is instrumental in the union between Claudio and his daughter, Hero. The governor has been informed of the conversation between Don Pedro and Claudio. He states, “No, no. We will hold it as a dream till it appear itself. But I will acquaint my daughter withal, that she may be the better prepared for an answer if peradventure this be true. Go you and tell her of it” (1.2.17-20). From this quote, the audience realizes that Leonato is wise and discrete; if he had acted on the information provided to him, he would have been in error.

Simultaneously, the audience was aware that nothing happens without Leonato’s awareness, thus highlighting his importance. The audience assumes that Leonato is in control and acts justly and cautiously. Thus, when Don John and Claudio betray Hero’s honor, the audience is cognizant of Leonato’s graciousness in the past and is able to identify with him. Leonato’s character matters, because without him the audience will not have a moral standard to judge the major characters.

Moreover, Leonato’s guiding hand is illustrated in his correction of Beatrice, his orphaned niece. It is Leonato that calls attention to the severity of Beatrice’s language. He argues, “By my troth, niece, thou wilt never get thee a husband if thou be so shrewd of thy tongue” (2.1.16-17). From these lines, the audience acknowledges Leonato to be a social standard. The audience realizes that he is straightforward in nature. Also, his words and responses are indicative of the correct form of communication; he is in a position of authority of what is socially acceptable and what is expected. Through Leonato, Beatrice’s inadequacies and abruptness in language are highlighted.

Furthermore, Leonato has the authority to give social advice to Hero. He urges, “Daughter, remember what I told you. If the Prince do solicit you in that kind, you know your answer” (2.1.55-56). Through these words, the audience recognizes the guiding hand of Leonato. He is motivated to keep his family on the right path. The audience draws the conclusion by analyzing Leonato’s words and responses, thus offering insight into his nature as a human being. Throughout the play, Leonato possesses the moral code and strives the do what is right and proper.

Furthermore, Leonato is important in the personal relationships of his relatives. It is Leonato who blesses the union between Claudio and Hero. He states, “Count, take of me my daughter, and with her my fortunes. His grace hath made the match, and all grace say amen to it” (2.1.263-265). From these lines, the moral code of Leonato is reaffirmed. The audience is able to judge Leonato by what he does. He shows kindness and concern; therefore, he is a good and upright man. Leonato is also instrumental in the union between Benedick and Beatrice. He participates in the deception that unites the couple. In the garden, he remarks:

No, nor I neither. But most wonderful that she [Beatrice] should dote on Signor Benedick, whom she hath in all outward behaviours seemed ever to abhor…By my troth, my lord, I cannot tell what to think of it. But that she loves him with an enraged affection, it is past the infinite of thought…I would have sworn it [her spirit] had, my lord, especially against Benedick. (2.3.89-91, 93-95, 108-109) From these quotes, the audience acknowledges that Leonato knows the difference between good and evil. He willingly deceives Benedick in order to achieve a greater good. In essence, Leonato knows what is best for Benedick and Beatrice even if they, themselves, do not. Thus, Leonato is able to adapt to the situation; he is a dynamic character.

Moreover, the governor is aware of his influence on social matters. Complementing Leonato’s age and perceived character, Benedick believes that Beatrice loves him because it is verbalized by Leonato. Benedick states, “I should think this is a gull, but that the white-bearded fellow speaks it. Knavery cannot, sure, hide himself in such reverence” (2.3.110-112). From these lines, the audience is reassured of Leonato’s character and moral standing. He is perceived by those around him to be a man of stature and authority. He is a respected and honest man; therefore, Benedick must believe what he overhears.

Also through these lines, the audience catches a glimpse of what Leonato looks like; we know that he is an older man. Benedick’s comment of Leonato’s “white-beard” makes the point clear. In sum, the audience is able to perceive Leonato’s importance and view what motivates the character.

Leonato’s importance is also highlighted in his interaction with other characters. The audience glimpses another view into the character of Leonato from his interaction with the Dogberry, the constable and Verges, the headborough. Despite the fact they are of a lower class, Leonato greets them with respect. Leonato says, “What would you with me, honest neighbour?...What is it, my good friends” (3.5.1, 7). In bidding them farewell, he remarks, “Drink some wine ere you go. Fare you well” (3.5.46). From these lines, the audience realizes Leonato is a good person, a moral standard. He treats the men with respect, thus adding insight into his character. Leonato epitomizes the social standard and creates the “mark” that all the other characters are judged against.

The roundness and dynamicity of Leonato comes to fruition during his words and responses to his daughter’s dishonor. When the unrealized marriage scene between Claudio and Hero takes place, the audience, through Leonato’s words and responses, recognizes the severity of the scene. Leonato, who has been so aware of the social dealings within his home, is at a loss for wisdom in words and responses. He asks Claudio, “What do you mean, my lord?” (4.1.41). He is devastated and argues, “Dear my lord, if you in your own proof [.] Have vanquished the resistance of her youth [.] And made defeat of her virginity—” (4.1.43-45). From these lines, the audience realizes that Leonato, the social standard, has lost all awareness. He gasps, “Are these things spoken, or do I but dream?” (4.1.64). From this line, the audience understands there is a loss of all social order. The governor cries, “O fate, take not away thy heavy hand. Death is the fairest cover for her shame [.] That may be wished for” (4.1.112-114). Through these lines, the audience recognizes the total reversal of Leonato’s character.

In previous scenes, the governor was wise and discrete; the audience is cognizant of the social chaos through Leonato’s words and responses. Leonato is fully alive and in pain; his plight is significant, because the author has established his importance.

Toward the end of the scene, Leonato begins to regain stability, and questions the major male characters as they relate to his daughter’s dishonor. He announces, “If they speak but truth of her [.] These hands shall tear her. If they wrong her honour [.] The proudest of them shall well hear of it. Time hath not yet so dried this blood of mine, Nor age so eat up my invention” (4.1.189-193). From these quotes, the audience realizes that Leonato is a force to be reckoned with, and the audience is aware of his multi-dimensionality within the play. Still, Leonato remains the sounding board for the audience. He represents the social standard and by him all other characters are measured.

Further highlighting his roundness and dynamicity, the governor provides the reader with a host of emotions and thus illuminates the plot of Hero, his daughter. Leonato states, “I pray thee [Antonio, his brother] cease thy counsel, Which falls into mine ears as profitless…Nor let no comforter delight mine ear [.] But such a one whose wrongs do suit with mine. Bring me a father that so loved his child” (5.1.3-4, 6-8). Through these lines, the audience understands the plight of Leonato and identifies with him. Through his grief, the audience remembers his character in previous scenes and cares about him.

Leonato’s words and responses allow the audience to further analyze his character and consider his motivation. Leonato is a concerned family man who promotes harmony and unity within his household. He possesses the essence of humanity.

Moreover, it is the governor who re-stabilizes in the play. He states, “My soul doth tell me Hero is belied, And that shall Claudio know, so shall the Prince, And all of them that thus dishonour her” (5.1.42-44). Also, it is Leonato that prevents Don Pedro and Claudio from leaving his residence until the truth is revealed.

He challenges Claudio. Leonato argues, “Tush, tush, man, never fleer and jest at me…Know Claudio to thy head, Thou hast so wronged mine innocent child and me [.] That I am forced to lay me reverence by…Do challenge thee to trial of a man. I say thou hast belied mine innocent child. Thy slander hath gone through and through her heart, And she lies buried with her ancestors” (5.1.58, 62-64, 66-69). From these quotes, the audience recognizes a change in emotional stability. Leonato is actively reasserting his authority. The social standard has been resurrected.

Leonato takes control of the situation and through his leadership Hero’s honor is restored. Toward the end of the play, the governor addresses the persons who aided Don John in his dishonorable scheme. He gnarls, “Art thou the slave that with thy breath hast killed Mine innocent child?” (5.1.247-248). From these lines, the audience envisions Leonato’s appearance as a man of authority and identifies with his motivations to preserve his daughter’s honor. In this scene, Leonato is illustrating his elite status and his position as a social authority. He heads the investigation, and the others follow his leadership. Leonato remains the social sounding board.

After clearing his daughter’s name, he boldly asserts, “So are the Prince and Claudio who accused her [.] Upon the error that you heard debated” (5.4.2-3). From this quote, the audience sees Leonato as an authentic character that fights for his family and justice. These are attributes that the audience readily reverences.

Furthermore, Leonato reaffirms his role as family guide, and he directs and orchestrates the actions of his relatives. He tells Hero and Beatrice, “Well, daughter, and you gentlewomen all, Withdraw into a chamber by yourselves, And when I send for you come hither masked. The Prince and Claudio promised by this hour. To visit me” (5.4.10-14). From these lines, the audience acknowledges that Leonato is back in control and all is well and back to normal. It is Leonato who possesses the guiding hand in which the major characters are directed. Without the governor, the plot could not have been feasible or successful.

In summary, Leonato, the governor of Messina, is instrumental in the movement and actions of the major characters of Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing. He provides the audience with a “mark” to measure the other characters. Through his words and responses, the audience senses his morality and importance. Being a round and dynamic character, Leonato is not expendable in the plot of Much Ado About Nothing. It is through his character that the plot becomes feasible and believable. The character of Leonato is instrumental in every major scene and interacts with every major character; without Leonato there could not have been a Much Ado About Nothing.

Weekly Literary Inspiration

There is only one success, to be able to spend your life in your own way. --Anonymous

11 October 2008

Shakespeare and Education (Shakespeare in Popular Culture)

In viewing the YouTube video Comic Relief - Catherine Tate & David Tennant during a Linguistics class, I realized that William Shakespeare is embedded within every aspect of the modern-day education. The video epitomizes the “Shakespeare omnipresence in our modern culture.” The sixteenth and seventeenth century poet and playwright engulf the educational criteria from England to American to the Middle East. Shakespeare is a world wide phenomenon with a timeless flare.

The British sitcom points to this phenomenon and timeless flare. Initially, a substitute professor enters the room. He asks the class to turn to a Shakespearean sonnet. A female student interrupts the progression of class by questioning his ability to teach the class; he is of Scottish descent. Furthermore, she insults Shakespeare and states he is “pointless, repetitious and dull.” At this moment, the English teacher loses his composure and vehemently defends Shakespeare as a genius.

Moreover, he insults the student and insinuates that she is not intelligent. Then, the student loses her composure and recites the sonnet in its entirety, thus reclaiming her credibility as a person to be reckoned with on the manner of Shakespeare. Shakespeare symbolizes excellence. It was presented in a comical way, but the sitcom epitomizes the ideals of Shakespeare within our culture.

The sitcom is indicative of the very comical way in which Shakespeare addressed issues within his culture. There is a dialogue exchanged between two people, going back and forth, with twisted and manipulated language. In the end, one force is overcome by the other and resolution is achieved. To piggy back on the sitcom, the Scottish teacher is able to teach the Elizabethan poetry because it was a part of “his” education as well; it is not just a component of a British education. He defends Shakespeare instead of defending his own heritage. Even after the matter of the female student has been resolved, the English teacher recites a few lines of Shakespeare as well. The unstated message is clear; Shakespeare belongs to everyone.

Also, the sitcom highlights the level of penetration that Shakespeare has achieved within the modern day education. Most people are able to remember Shakespeare being taught, in some fashion, in elementary school. None would deny that they can remember every grade level, after elementary school, addressing some piece of Shakespeare. In order to obtain a college degree, despite your major, you are exposed to Shakespeare. Shakespeare is all around us, but he is especially predominating within our modern day educational system.

In essence, William Shakespeare has been and seemingly will be a continual presence in a variety of cultures. The way he uses language is intriguing and attracts all cultures for its sheer creativity. The plots are still compelling today because they are timeless. William Shakespeare has made an indelible mark on popular culture, but he is most loved with the field of educational excellence.

Please see links column for the YouTube video. It is located under Shakespeare and Popular Culture.

09 October 2008

Shakespeare Rationale 1 Henry IV 2.4 lines 19-84: Passionate Discourse and Hurt Feelings (Shakespeare)

The context of the moment is very important in the scene. If, the reader had not been allowed to read the letter along with Hotspur, the emotion of the scene would have been different. The interaction between Hotspur and his wife becomes an intriguing one because of the context. In Act 2.4, after Hotspur reads the letter, it is obvious that he is spirited and he is preparing for battle. He states, “Hang him! Let him tell the King we are prepared; I will set forward tonight” (1207). Then his wife, Lady Percy, enters the room and the mood changes immediately. He informs her of his need to leave their home within hours.

Lady Percy begins addressing him in a sweet and seductive manner. She asks, “For what offence have I this fortnight been a banished woman from my Harry’s bed?” The language of the text changes; it seems as if her address is to be read as poetry, not prose. She seems to speak to him in a loving manner at this point of the dialogue. I imagine that she is touching or stroking him in some manner. There definitely should be body contact in order for the message to be made clearer. Hotspur does not acknowledge her pleas for him to stay home. Instead, he calls for the servant.

Then, she asks him to hear what she is saying. She states, “But hear you, my lord.” Only then does he acknowledge her, he asks, “What sayst thou, my lady?” I believe he is a bit annoyed by her questions and he lies to her. Then abruptly the mood changes. This should be reflected in the stage lighting as well, in order to bring attention to the next transactions in dialogue. Lady Percy no longer acts as a lady. She knows that her husband is lying. Her tone changes. She remarks, “Out, you mad-headed ape!...In faith, I’ll know your business, Harry, that I will.” Her body language as well as her voice must change in order to highlight her discontent.

Next, she calls him on his lie and states the real reason that he is leaving. She states, “I fear my brother Mortimer…hath sent for you to line his enterprise.” Then, she threatens him, she argues, “…but if you go---.” Next she degrades him, by saying, “Come, come, you paraquito, answer me.” It is an insult. She knows Hotspur is often hot tempered and speaks when he should not. She is calling him out on his weaknesses of character.

Moreover, she makes another threat. She remarks, “In faith, I’ll break thy little finger, Harry, An if thou will not tell me all things true.” The statement can be a threat and insult. The threat of disfiguring his “manhood”, but the insult of calling his “manhood” little.

Finally, Hotspur reacts in a violent manner. He barks, “Away, away, you trifler! Love? I love thee not, I care not for thee, Kate.” He responds in a manner that he hopes would injure her in some fashion. Whether she shows any reaction to his assault would be an indicator of her true nature. Is she hurt, or is she unshaken? That is an important question.

07 October 2008

Compare/Contrast Pre-Islamic Poetry and 20th Century Middle Eastern Poetry (Middle Eastern Literature)

Pre-Islamic poetry and 20th Century Middle Eastern poetry remarkably possess similar themes and utilizes effective language. Despite these similarities, they also demonstrate distinctive differences as well. Pre-Islamic poetry is considered to exist among a pagan society in Middle East, before the rise and spread of Islam.

“The Poem of Imru-Ul-Quais” is believed to have been written before 622 C.E.. Whereas, 20th-Century Middle Eastern poetry, of course, is the modern-day poetry of the era in which we are living. Nizar Qabbani’s poem, “Jerusalem,” is indicative of this 20th-Century poetry. Despite the time lapses, many comparisons and contrasts can be made between the language and rhetorical devices of Pre-Islamic and Modern-day Middle Eastern poetry.

In analyzing “The Poem of Imru-Ul-Quais,” a well known Pre-Islamic poem of Arabia, one immediately realizes the effective use of language. The tone of the poem is subjective and focused on the poet and his feelings; no religious reference is made. The poem is distinctively descriptive and sometimes musical. The themes are love, egotism, nature, and pain. Furthermore, the poem uses many rhetorical devices, but the most prominent is simile and anaphora.

First, the descriptive language of the poem is conveyed within the lines. In describing his lost love, the poet remarks:

She was slender of waist, and full in the ankle. / Thin-waisted, white-skinned, slender of body, / her breast shining polished like a mirror. / In complexion she is like the first egg of the ostrich---white, mixed with yellow. (58-61)

The poet places a great deal of detail in the description of his love. Moreover, he uses descriptive language to explain the physical attributes of his horse. He states:

Well-bred was he, long-bodied, outstripping the wild beasts in speed / Bay-colored, and so smooth the saddle slips from him, as the rain from a smooth stone, / Thin but full of life, fire boils within him like the snorting of a boiling kettle; / He has the flanks of a buck, the legs of an ostrich, and the gallop of a wolf. (92, 94-95, 99)

The descriptive language is compelling and effective. It provides the words into visual pictures for the reader.

Second, the lines are sometimes musical as well. The poet seems to be aware that a certain combination of words can create a distinction in sound. One line demonstrates the technique more than any other. In line 46 the poets states, “Many a fair one, whose tent can not be sought by others, have I enjoyed playing with.” The line is musical, especially if it is read as an iambic line.

Moreover, the theme of love gleams the lines of the poem. The poet makes several references to his present and past loves. The first line asks the reader to “stop, oh my friends, let us pause to weep over the remembrance of my beloved.” Next, he remarks, “The follies of men cease with youth, but my heart does not cease to love you” (79). References of the love the poet feels is intertwined within the entire poem. Love is the major theme.

Also, a coherent theme of the poem is the subjective and egotistical stance of the poet. It is blatant to the reader. Not only is the poet often egotistical, he is somewhat arrogant as well. In line 46, he states, “Many a fair one, whose tent can not be sought by others, have I enjoyed playing with.” Next, he explains he has spent “many pleasant days…with fair women / Many a beautiful woman like you, Oh Unaizah, have I visited at night ” (21, 35).

Another theme is the impact of nature in the poet’s environment. He describes many different settings of the landscape. First, he comments, “I stood in the gardens of our tribe, / Amid the acacia-shrubs where my eyes were blinded with tears by the smart from the bursting pods of colocynth” (7-9).

Next, he mentions, “The South wind blows the sand over them the North wind sweeps it away” (4). Finally, he references, “I sat down with my companions and watched the lightning and the coming storm / So mighty was the storm that it hurled upon their faces the huge kanahbul trees,” (114, 117). Through these lines, the reader realizes the impact of nature on the poet’s life.

The last important theme is pain. The poet’s pain is caused by the loss of his love. The poet states, “As I lament in the place made desolate, my friends stop their camels; / They cry to me “Do not die of grief; bear this sorrow patiently.” / Nay, the cure of my sorrow must come from gushing tears” (10-12).

Furthermore, he explains, “Thus the tears flowed down on my breast, remembering the days of love; / The tears wetted even my sword-belt, so tender was my love” (19-20). In essence, the poet expression of pain is intertwined within the lines of the poem, alongside the love that he once felt for his lost love.

Aside for the language and themes, the poem utilizes a host of rhetorical devices. The most prominent is simile which is evident within the lines of “The Poem of Imru-Ul-Quais.” Many examples can be found within the poem. Most poignant, the poet remarks, “Fair were they also, diffusing the odor of musk as they moved, / Like the soft zephyr bringing with it the scent of the clove” (17-18).

Then, he states, “The fat was woven with the lean like loose fringes of white twisted silk” (28). Next, he explains, “She turns away, and shows her smooth cheek, forbidding with a glancing eye, / Like that of a wild animal, with young, in the desert of Wajrah. / And shows a neck like the neck of a white deer” (63-65).

When describing his love, the poet recalls, “Her form is like the stem of a palm-tree bending over from the weight of its fruit” (72). The poet describes his love; he states, “In the evening she brightens the darkness, as if she were the light-tower of a monk” (76). When addressing the encampment of his love, he recalls, “The dung of the wild deer lies there thick as the seeds of pepper” (6). Simile is a major component of the poem.

Also, the poet uses anaphora as a rhetorical device. In the last lines of the poem, a clear example of anaphora is epitomized. He announces:

As though a Yemani merchant were spreading out all the rich clothes from his trunks, / As though the little birds of the valley of Jiwana awakened in the morning / As though all the wild beasts has been covered with sand and mud, like the onion’s root bulbs / They were drowned and lost in the depths of the desert at evening. (126-127, 129-130)

The poet draws emphasis to the last line of the poem by using anaphora. It is an effective and timeless use of language which is still effective today.

In 20th-Century Middle Eastern poetry, the same analysis can be applied. In analyzing Qabbani’s “Jerusalem,” one also immediately recognizes the effective use of language. However, there is one striking difference; the poem has a religious tone. The poem is distinctively descriptive.

However, instead of the major theme being love; overwhelmingly, the prevalent themes are pain, doubt, and hope. Furthermore, the poem uses many rhetorical devices, but the most prominent is metaphor, anaphora, personification and the rhetorical question.

First, the descriptive language of the poem is conveyed within the lines. By describing his sorrow and pain, the poet remarks, “I wept until my tears were dry / I prayed until the candles flickered / I knelt until the floor creaked” (1-3). The opening lines are powerful and indicative of the effective use of descriptive language. Also, the poet effectively combines descriptive language and repetition to evoke powerful imagery for the reader. He states:

City of the virgin, your eyes are sad / City swathed in black, who’ll ring the bells / City of sorrows, a huge tear / Jerusalem, beloved city of mine / My city, city of olives and peace. (9, 13, 17, 22, 30)

The language is thought-provoking as well as image-provoking. The poet understands how language can affect the reader.

The major themes of the poem are pain, doubt and hope. The poet expresses these themes through metaphor, anaphora, personification and the rhetorical question. He states, “Jerusalem, you of the myriad minarets, / become a beautiful little girl with burned fingers” (7-8). This is a poignant metaphor of pain and suffering. The writer speaks of a society in which its children are burned, disfigured. Next, he conveys pain and doubt through the anaphora and the rhetorical question. He asks:

City swathed in black, who’ll ring the bells / Who will carry toys to children / Who’ll save the Bible? / Who’ll save the Qur’an? / Who will save Christ, who will save man?

The message of pain and doubt is evident to the reader. Though the images, pathos is achieved. Next, the poet uses personification to expand on the themes of pain and doubt. He notes, “The stones of your streets grow sad” (11). Finally through personification, he gives the reader a shimmer of hope. He states: “Jerusalem, beloved city of mine, / Tomorrow you lemon trees will bloom, / your green stalks and branches rise up joyful, / and your eyes will laugh” (22-25).

In summary, Pre-Islamic and 20th Century Poetry can not be read by Western standards. It has its own beauty and form. The reader can not look for iambic pentameter, or rhymes schemes; the reader must place close attention to the imagery displayed the use of descriptive language and rhetorical devices. Although very different in length, structure, ideology, and religious reference, “The Poem of Imru-Ul-Quais” and “Jerusalem” possess many similarities in the usage of effective language.

03 October 2008

“The Life You Save May Be Your Own” by Flannery O’Connor (Southern Literature)

The “heart of the story” lies with the possibility of transformation in Mr. Tom T. Shiftlet. He is a wanderer. He approaches the home of an old woman and her mute daughter, Lucynell Crater, as the sun is setting. They live on a dilapidated plantation that is in need of repair. The old woman does not see him as a threat. The woman attempts to marry off her mute daughter by offering him material gain. She wanted someone to aid her in the maintenance of the estate. The transformation of Mr. Shiftlet occurs in three parts as they relate to Lucynell.

Initially, he rejects the mute woman. It is only after he envisions material gain that he considers the young woman. He states, he “always wanted an automobile but he had never been able to afford one before.” He moves into their home. Then he marries Lucynell. He does maintenance around the estate and on the car and teaches Lucynell a word. He leaves her in the end. He is not whole physically or emotionally; he is missing part of his left arm. If he had chosen to remain with Lucynell they could have filled the voids within their lives. They could have met each other’s needs.

Weekly Literary Inspiration

You can stand tall without standing on someone. You can be a victor without having victims. --Harriet Woods

02 October 2008

The Epic of Son-Jara (African Literature)

The women in “The Epic of Son-Jara” could not be side-lined and excluded from the struggle for power. The roles played by women in the epic were extensive for the finality of Son-Jara coming to power. The Buffalo Woman, Du Kamisa, overwhelmingly coordinated of the birth of Son-Jara. Through Du Kamisa, Son-Jara came into existence; the Buffalo Woman orchestrated the entire event.

Examples of this can be found in the beginning of the text, the Tarawere brothers came seeking information on how to kill the Wild Buffalo Woman. She explained everything that had to be done in order for the Tarawere brothers to be successful. She provided the talking dog and instructed the brothers to choose the ugly maiden, Sugulun Konde. Du Kamisa of Du arranged to have her sister, Sugulun Konde, chosen by the Tarawere brothers. She was the "shadow" directing the birth of Son-Jara.

In examining the role of Sugulun Konde, Son-Jara’s mother, one noticed feminine “occult” power as well. Sugulun Konde prevented the Tarawere brother’s from laying with her. She told the elder brother “her husband was in the Manden and so was his wife.” The elder Tarawere brother stated Sugulun Konde was shorter and smaller than other women but she was able to use her occult power to prevent his advances.

After the birth of Son-Jara, his mother was mistreated because of his disability. Once exhausted by the mistreatment, she sparked Son-Jara to walk. She was the initiator of his “new birth.” She looked after him. In the case of the Boatman patriarch, she made the agreement with the bracelet.

The agreement was essential in Son-Jara crossing the river and taking control of the Manden. Please remember it was the feminine power of his mother that allowed Son-Jara to walk. She went to her god and petitioned for Son-Jara. It was the staff that she made from the apple custard tree that enabled Son-Jara to walk after nine years.

Once exiled, Son-Jara was guided by another feminine power, the nine Witches of Darkness. These women practiced magic and helped Son-Jara stock-pile occult power. They made their allegiance to him after he proved himself by seizing nine buffalos.

The next woman to aid Son-Jara was his sister, Sugulun Kulunkan. She offered to seduce Sumamuru to get the secrets of his “occult power.” She was successful and with the information she provided Son-Jara, he succeeded against Sumamuru.

Son-Jara’s mother died only after Son-Jara no longer needed her protection. To examine other feminine powers, we can not forget the powers against Son-Jara. His step-mother asked her Holy man to cripple Son-Jara. She was also the cause of his exile and the reason he was repeatedly turned away from refuge (for fear of retaliation). The women in Son-Jara’s life were instrumental in his rise to power as the King of the Manden.

"The Epic of Son-Jara" is a wonderful read. The Jabete tribe in Mali recites the epic every seven years. I hope to be in attendance at least once in my lifetime.

01 October 2008

A Response to Booth’s Rhetorical Stance (Rhetorical Theory)

Several statements with the text provoke complex thoughts, but the most poignant statement states, “Rhetoric is the art of finding and employing the most effective means of persuasion.” Then Booth remarks, “Nobody writes rhetoric, just as nobody ever writes writing.” What is his point? What is the argument? I do not know whether I disagree or agree with the statement. Moreover, he asserts, “rhetoric at best is very chancy…Successful rhetoricians are…born, not made.” I definitely agree with this assertion, but I am not sure why. Do I have a scientific basis for this belief or is it a biased opinion?

Booth goes on to explain the importance of rhetoric in a serious and “persuasive” manner, by maintaining a “rhetorical balance.” Rhetorical balance is an absolute in teaching rhetoric and its survival as a rhetorical form. He believes in his argument and his passion echoes throughout the text. In essence, the text is persuading you to believe the argument; you become “falling prey” to Booth’s rhetoric. Furthermore, he is methodical and systematic, similar to Aristotle. Booth outlines three major points within the text, two of which “stand out” to me, the reader.

Booth’s first stance is “the pedant’s stance.” The pedant’s stance occurs when the rhetorician betrays the audience by “writ[ing] not for the readers but for bibliographies.” The rhetorician mistakenly foregoes the audience and concentrates simply on the information and the argument. We must, as Booth states, “[have a] personal relationship [between the] speaker and [the] audience.” He proves his argument or point by using stories to expand the understanding of the reader.

Booth’s third stance is the “entertainer’s stance” and it “stands out” as well. Booth describes it as the “willingness to sacrifice substance to personality and charm.” Instead of forgoing the audience for the argument, the “entertainer’s stance” forgoes the argument for the audience. The rhetorician is attempting to win the audience through “empty colorfulness.” Again, he proves his argument or point by using stories to expand the understanding of the reader.

In essence, Booth presents the extremes of rhetoric and the naïve mistakes students of rhetoric often make by not maintaining proper balance. The proper balance means that one is able to make “...the available arguments about the subject itself; the interests and peculiarities of the audience; and the voice, the implied character, of the speaker.” Booth stresses that rhetoric is an art and must be done correctly; otherwise the art will be lost.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)